Florian Freitag (Duisburg-Essen)

The impact of COVID-19 on tourism in general and on theme parks in particular has been immense. While we may not yet be able to assess and understand the full economic implications of the pandemic for the global theme park industry, its cultural impact e.g. on how visitors interact with theme park landscapes and on the ways theme parks present themselves in so-called paratexts (from Greek pará-, “beside, adjacent to,” and “beyond, or distinct from, but analogous to”; texts that accompany literary or other medial texts; see Genette and Gray) has already become readily apparent. With respect to the former issue, for instance, Europa-Park (Rust, Germany) has introduced new features on its website and app that allow visitors to schedule park visits and time slots for specific rides. Partly mandatory (park tickets must be booked in advance for a specific date), these features have markedly increased not only the amount of “Spaß-Arbeit” (fun work; see Legnaro, p. 293) or “Erlebnisarbeit” (experience work; see Kagelmann, p. 175) that visitors need to invest in their park visit but also the general relevance of theme park paratexts – i.e., medial representations of the theme park or its parts that are produced by the park itself and that serve as a medial interface between the park landscape and the visitors, providing the latter with “frames and filters” or “scripts” on how to experience the park.

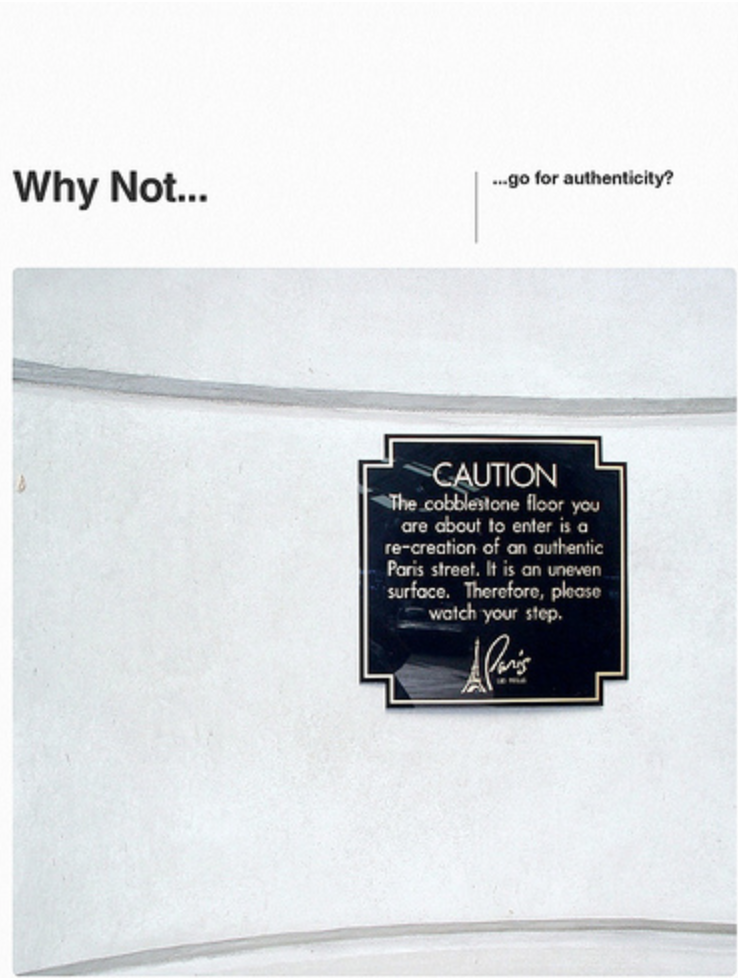

At the same time, the example of Europa-Park also illustrates the impact of the pandemic on yet another genre of theme park, namely, advertisements. Seeking to mitigate the disastrous effects of forced park closures and pandemic-related travel bans on park attendance, posters and social media posts in the context of Europa-Park’s Summer 2020 ad campaign have highlighted the “metatouristic” potential of the site, thus indicating a renewed emphasis on a theming strategy that had been particularly popular during the 1980s and 1990s. Though it is the large, multimedia conglomerate-owned parks which are best known for drawing on established media franchises as the source of their theming – for instance, the use of the Harry Potter franchise in Universal Studios parks – regional and family-owned parks like Europa-Park have also adapted established media franchises into themed areas, for instance in the “Arthur”-themed area, based on the Arthur et les Minimoys-movie trilogy, which opened in 2014. Rather than advertising the site as a destination for film or, more generally, fictional media tourism, however, Europa-Park’s 2020 “Urlaub in Europa” (holiday in Europe) campaign has returned to foregrounding the park’s “metatouristic” appeal (Köck, p. 14). For instance, “Urlaub in Europa” billboards e.g. at train stations in southern Germany show postcards – yet another theme park paratext – that combine close-ups of a replica of a famous tourist sight in one of the park’s themed sections (an Andalusian cityscape, the Colosseum, a Scandinavian fishing village, or a Greek temple) with a shot of a family enjoying a dinner or a group of people taking a guided tour or a picture of a hotel room ready for occupation. The postcards are framed by the Spanish, Italian, Norwegian, or Greek national flags respectively, and are held by a hand so that they perfectly align with larger, blurred versions of the “tourist sight” shots in the background – no doubt in order to authenticate the tourist’s presence at the actual sites. It is only upon closer inspection, however, that passersby realize that far from inviting them to travel to Spain, Italy, Norway, or Greece – which due to Coronavirus and related travel restrictions would not be advisable or even possible anyways – the billboards rather seek to entice them to visit the “replicas” of these and other countries at Europa-Park.

Online, the campaign employs a similar strategy: posting pictures of its themed areas on its Instagram profile, for instance, Europa-Park asks its followers “Are you in [the Netherlands] or in the Dutch themed area at #EuropaPark?” and invites them to “Tag a friend who wants to visit Spain! Maybe you can convince them to come to South-Germany instead [winking emoji]”.

To be sure, over the course of its 45-year history (the park was opened on 12 July 1975), Europa-Park’s promotional campaigns have frequently advertised visits to the site as a cheaper and more convenient alternative to journeys to the actual places referred to in the park. For instance, in 1994 – and thus a year before the Schengen Agreement became effective and passport controls at most borders between (Western) European countries were abolished – the park adopted the slogan “Spaß ohne Grenzen” (“limitless fun” or “fun without borders”). With the COVID-19 pandemic not merely subjecting tourists to border checks, but making leisure travel to many European tourist destinations actually impossible during the early summer, however, the “Urlaub in Europa” campaign has more explicitly and seriously than ever before marketed Europa-Park as a site of metatourism – i.e., as a surrogate destination, a place where you (physically) travel in order to (imaginatively) travel somewhere else, and where “the tourist experience of another culture has become a tourist experience in itself” (Carson, p. 232).

Metatouristic theming had become particularly popular among theme parks during the 1980s and 1990s. The year 1982, for instance, saw the opening of EPCOT Center (later renamed Epcot) at Walt Disney World Resort with its “World Showcase,” each of whose nine “pavilions” is dedicated to a North American, European, Asian, and African country. The very same year, Europa-Park opened the first of its now altogether 15 sections themed to European countries, namely, Italy, which was soon followed by the Netherlands (1984), Switzerland (1985), England (1988), and France (1989). During the early 1990s, an entire series of so-called “gaikoku mura” (“foreign country villages”) opened in Japan, all of which referred to a specific (mostly European or North American) country. Examples include Oranda Mura (dedicated to the Netherlands and opened in Sasebo in 1983), Glückskönigreich (Germany, Obihiro, 1989), Niigata Russian Village (Russia, Agano, 1993), and Parque Espana (Spain, Shima, 1994; see Raz, p. 148-53; Hendry). And while metatouristic theming soon gave way to IP-based thematic sources, that is, sources such as movie franchises, it would return with the pandemic, at least in Europa-Park’s advertising campaign.

I visited

I visited